As sure as the sun rises in the East and sets in the West, modern¹ Russian wars begin in a dog’s dinner of disruption and disarray. From the naked aggression of Peter the Great in 1700 against the Swedish Empire² to the present “Special Military Action” that began with significant Russian rollbacks along the entire front, except Crimea, every modern Russian war witnesses their army fall into a fog of confusion and calamity in the first weeks, months even years against their foe.

As sure as the sun rises in the East and sets in the West, modern¹ Russian wars begin in a dog’s dinner of disruption and disarray. From the naked aggression of Peter the Great in 1700 against the Swedish Empire² to the present “Special Military Action” that began with significant Russian rollbacks along the entire front, except Crimea, every modern Russian war witnesses their army fall into a fog of confusion and calamity in the first weeks, months even years against their foe.

Just as certain as rains are to Ireland and ice and snow are to Siberia, however, the Russian army, general staff, politicians and the populace united remain innovative, cunning and intellectually agile: native, instinctual qualities in Russians that are not to be underestimated. Recall, Russia put the first human into space! Just like every other nation, Russian generals come in all stripes. But Russia’s special genius consistently germinates what I call the “learning general.” A learning general makes mistakes, often grievous ones. His hallmark, however, is simple: he never makes the same mistake twice, thereby transmuting fear of failure into audacity in the face of risk and ultimately into victory.

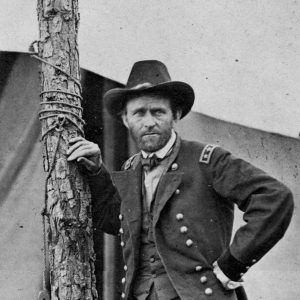

Ulysses S. Grant personifies the modern American example of how devastating a learning general can be. (George Washington was also a learning general.) Patton, Bradley, MacArthur, and Eisenhower were all operationally competent, but not a one of them was a learning general like Sam Grant.

A mediocre student at West Point but something of a standout in the Mexican-American War, Grant was ejected from the army while garrisoning California. All he subsequently touched as a civilian ended in failure, once even reduced to chopping and hauling wood into town that he might, at the very least, feed his family. Of course there is the old lamentable slander that Grant was a drunk, but drunks win wars not.

A mediocre student at West Point but something of a standout in the Mexican-American War, Grant was ejected from the army while garrisoning California. All he subsequently touched as a civilian ended in failure, once even reduced to chopping and hauling wood into town that he might, at the very least, feed his family. Of course there is the old lamentable slander that Grant was a drunk, but drunks win wars not.

After the April 12, 1861 assault on Ft. Sumter, Grant quickly sought a renewed post in the army. He said, “there are but two parties now. Traitors and Patriots.”³ With the help of Rep. Elihu Washburne, Grant was commissioned a colonel in command of 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment on June 14, 1861. By August 5 he was Brigadier General of volunteers. Within months he had captured Paducah, Kentucky, and soon displaced General Fremont. Quickly sizing up his enemy, he beat him handily at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. Ft. Donelson on the Cumberland River was another matter.

First, Grant underestimated enemy strength but quickly recovered, not, however before he failed to close his right flank allowing Nathan Bedford Forest and 700 men to escape. Gathering more forces in defiance of his commanding officer Henry Halleck he soon bulldozed Ft. Donelson into “unconditional and immediate surrender” on February 16, 1862. Grant’s was the first major victory in the American Civil War and he was promoted to Major General by President Lincoln during the week of March 3, 1862.

At Shiloh Grant failed to order his soldiers to entrench in the face of heavy Confederate reinforcements. Unprepared for a bloody Confederate surprise attack, it was only after consulting Sherman that he won the next day with a bold counterstroke that sacrificed thousands. Later in the war came the slaughter at Cold Harbor, followed by an attack on World War One type enfilading fields of fire that destroyed 85% of a Maine regiment in less than twenty minutes at Petersburg. Lastly, the Battle of the Crater.

Grant rose to the highest of commands not in spite of his mistakes, but because he never made the same mistake twice: the defining quality of a learning general. Most men cannot handle a single failure in life. But of life’s most valuable lessons, learning from failure, is the most salutary of all. A general who learns from his mistakes soon grows confident and mature in the face of risk. And with confidence growing the battlefield becomes an enemy boneyard. By the close of the war Grant captured three armies, one at Ft. Donelson, one at Vicksburg and one at Appomattox. He missed a fourth by a whisker at Chattanooga.

***

Three great wars. Three catastrophic beginnings. Three exemplary victories. The Great Northern War of 1700-1721, Napoleon’s Grand Armée of 1812 and the great hubris of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941. Each war birthed in calamity. Each war culminated in total victory. Each won by a learning general.

It is commonplace to view the wars of Russia’s past through the prism of craquelure, but this view is in error. The Great Northern War fought between 1700-1721 is as relevant now as it was in 1812 or 1941.

In 1700 Peter the Great invaded the Swedish Empire with an army reformed along European lines. Gone were the steppe warriors, the streltsy, a rag tag feudal lot armed with a pike and an arquebus. Their hereditary forebears, mounted archers, defeated the Mongols at their own game. (Even then the Russians were a learning lot.) Peter’s new model army exchanged Parthian shot† for musket barrage and charge of cold steel.

The war began well for the Swedes, poorly for the Russians. The first battle at Narva, November 30, 1700 was a disaster in every way, except one. Peter’s command structure was a tapestry of confusion. Seeking reinforcements Peter was not even on the field of battle when Charles XII, king of Sweden arrived. Moreover, Peter’s army was too green: entire regiments fell, raked by musket and cannon balls, retreating ignominiously within earshot of the enemy howls of a bayonet charge. Only the Preobrezhinksy and Semyenovsky Regiments held fast, formed squares and fought on while the other twenty-nine regiments of Peter’s army surrendered to Charles XII.Preternaturally gifted towards warfare Charles XII destroyed Peter’s allies, ad seriatim, forcing a separate peace on both Denmark-Norway and the Saxon-Polish-Lithuanians by 1707. Meanwhile, Peter learned many a hard lesson, but three will suffice: he simplified his command structure, he blooded his armies, and finally, beguiled would-be invaders in and then scorched the earth. Charles XII, emboldened by his victories over Peter’s allies invaded Russia in 1708. Peter retreated into the vastness of mother Russia until the winter of 1708/09 arrived. For the first, but not last time, the cold arctic air manifested two of Russia’s most unforgiving generals: January and February. By spring’s arrival Charles XII’s supply lines were dangerously over-extended, his army near exhaustion. Nine years after his Swedish land grab, Peter led his army to victory over Charles XII at the Battle of Poltava on July 8 1709. Although the war between the Sweden and Russia was not officially over, Poltava was decisive and had so disrupted the balance of power in central Europe that his original allies (self-aggrandizers who had signed a separate peace with Sweden) rejoined the fight so as to grab their piece of the once formidable Swedish Empire.‡

One-hundred and three years later, on June 24, 1812 Napoleon crossed the Niemen River into Russia with 450,000 men under arms. The flat-footed Russian High Command had no answer to this brazen act of aggression. After weeks of forced marches Napoleon won at Vitebsk and then smashed whatever confidence Russian General Barclay de Tolly had left when he captured the fortress city of Smolensk. Russian General Bagration (actually a Georgian) was faulted for not relieving Barclay de Tolly and both were sacked in favor of veteran of the Ottoman wars, Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov. Kutzov, loathed by the Czar Alexander I, learned the art of war after multiple blunders in three Russo-Turkish wars which preoccupied Russia prior to Napoleon’s invasion. Napoleon’s troubles soon began in earnest as Kutuzov employed scorched earth tactics and near-guerilla style attritional warfare against Napoleon and his Marshals. Weeks more of forced marches befell Napoleon’s Grand Armée, until Kutuzov wheeled around on September 7, 1812 at Borodino and fought Napoleon. It was a bloody Pyrrhic victory for the French. The Russian army survived intact to fight another day. Seven days later Napoleon and his now depleted army of 100,000 captured an arson-scorched Moscow. Napoleon howled imprecations at the Czar as Moscow burned, “the barbarians, the savages, to burn their city like this! What could their enemies do that was worse than this? They will earn the curses of posterity.”¤ His logistics shattered, Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, losing all but 35,000 of his once 450,000 strong army. Napoleon’s aura on invincibility destroyed, Kutuzov’s army had turned the tide.

One-hundred and three years later, on June 24, 1812 Napoleon crossed the Niemen River into Russia with 450,000 men under arms. The flat-footed Russian High Command had no answer to this brazen act of aggression. After weeks of forced marches Napoleon won at Vitebsk and then smashed whatever confidence Russian General Barclay de Tolly had left when he captured the fortress city of Smolensk. Russian General Bagration (actually a Georgian) was faulted for not relieving Barclay de Tolly and both were sacked in favor of veteran of the Ottoman wars, Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov. Kutzov, loathed by the Czar Alexander I, learned the art of war after multiple blunders in three Russo-Turkish wars which preoccupied Russia prior to Napoleon’s invasion. Napoleon’s troubles soon began in earnest as Kutuzov employed scorched earth tactics and near-guerilla style attritional warfare against Napoleon and his Marshals. Weeks more of forced marches befell Napoleon’s Grand Armée, until Kutuzov wheeled around on September 7, 1812 at Borodino and fought Napoleon. It was a bloody Pyrrhic victory for the French. The Russian army survived intact to fight another day. Seven days later Napoleon and his now depleted army of 100,000 captured an arson-scorched Moscow. Napoleon howled imprecations at the Czar as Moscow burned, “the barbarians, the savages, to burn their city like this! What could their enemies do that was worse than this? They will earn the curses of posterity.”¤ His logistics shattered, Napoleon had no choice but to retreat, losing all but 35,000 of his once 450,000 strong army. Napoleon’s aura on invincibility destroyed, Kutuzov’s army had turned the tide.

Fast forward, in the argot of internet America, one-hundred twenty-eight years, three-hundred and sixty-three days to June 22, 1941. Three million, eight hundred thousand men, three-thousand seven-hundred ninety-five tanks, twenty-three thousand pieces of artillery, over thirty-thousand mortars, five-thousand six-hundred and seventy-nine aircraft and over one-million two-hundred thousand horses and vehicles under the aegis of Operation Barbarossa invade the Soviet Union. Their objective was the A-A line, a straight line running from Archangelsk to Astrakhan. Lebensraum. By late August Kiev had fallen, soon too had Minsk and the Baltic states. Leningrad was besieged. All of the crucial Donbass region gone and so too the Sea of Azov. Army Chief of Staff, Zhukov was sacked and sent to the rear to command reserves. The Wehrmacht’s Operation Typhoon came within 87 miles of Moscow in late September when Stalin threw 800,000 (83 divisions) men at the Germans. Only 25 of the divisions were at effective strength, but they were just enough to hold the Germans to within 15 miles of the capital. Multiple crack Siberian divisions, who had beaten the Japanese at Khalkin Gol, counterattacked and drove the Germans back a hundred miles. With supply lines and entire army groups in disarray Hitler order retrenchment and reorganization. The drive to Moscow ground to a halt.

In desperation, Stalin recalls his most effective general to plan a new counter-offensive. Striding onto center stage comes the titan: one Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov. His early failures during Operation Barbarossa hardened him and prepared him to deal with the capricious autocrat Stalin. He quickly conceived Operation Uranus (Stalingrad) and Mars (Rzhev Salient) and put them into motion simultaneously. His double envelopment of Paulus’ Sixth Army at Stalingrad conjured the ghost of Hannibal at Cannae, 2,140 years before. But the Battle of the Rzhev Salient was an operational defeat. Lesson learned: no multiple operations simultaneously. A learning general, Zhukov then went on to best the tactics and strategy of Hannibal at Cannae a second time laying a well-prepared trap the along the Kursk Salient.

In desperation, Stalin recalls his most effective general to plan a new counter-offensive. Striding onto center stage comes the titan: one Georgi Konstantinovich Zhukov. His early failures during Operation Barbarossa hardened him and prepared him to deal with the capricious autocrat Stalin. He quickly conceived Operation Uranus (Stalingrad) and Mars (Rzhev Salient) and put them into motion simultaneously. His double envelopment of Paulus’ Sixth Army at Stalingrad conjured the ghost of Hannibal at Cannae, 2,140 years before. But the Battle of the Rzhev Salient was an operational defeat. Lesson learned: no multiple operations simultaneously. A learning general, Zhukov then went on to best the tactics and strategy of Hannibal at Cannae a second time laying a well-prepared trap the along the Kursk Salient.

Some scholars claim the idea of a trap at Kursk was General Rossokovsky’s idea. But I believe that to be untrue. The idea, aforementioned, was developed by Zhukov who brooded over the failure of the Rzhev Salient during Operation Mars. He learned from that mistake and employed the lesson at Kursk. Here, finally, was the epic battle of World War Two; the Poltava, the Borodino, Maloyaroslavets, Vyazma and Berizina campaign. Here, the Soviets ripped the guts out of the Wehrmacht and decided the fate of the Nazis. It remains the single largest battle in the history of human warfare. The entire Soviet populace within a hundred miles participated weeks before in laying the trap for the Nazis. Mothers and sons dug tank traps, ditches, machine gun and mortar nests, wrangled murder holes out of raw concrete just laid. This they did for their husbands, fathers, elder sisters and brothers all of whom were manning tanks, mortars, rifles, machine guns, artillery and planes. At Kursk the Russians gave no quarter to the Nazis and zero magnanimity in their defeat. It was total war and mass slaughter on a scale not even I want to contemplate.

***

Charles XII can be forgiven for invading Russia. No precedent existed for Russia’s behavior, especially in a Westphalian world order. But for Napoleon the precedent was all too clear. Hubris makes fools of great and evil men alike. Napoleon is the rule, not the exception. The same can be said of Hitler. His actions uncorked the rule, just as Odysseus’ shipmates uncorked and subsequently reaped the whirlwind.

Aside from Russia’s propensity to propel learning generals to the fore, there is another theme running, unsaid, through these three wars. Three wars saw their vital interests, existential in nature, threatened. How did Russia win such violent, destructive wars that laid waste to thousands of miles and killed millions of people? The question of Russian grand strategy and why they are fighting in the Ukraine will be addressed in my next post. Until then, a Russian proverb, a hint: “All Roads lead to Rome, but the road to Moscow is a matter of choice.”

Choice indeed.

———–Footnotes———-

1: Modern Russia begins when Peter the Great inserted his nation into the Westphalian System upon entering the Great Northern War of 1700-1721.

2: At the time, the Baltic was a Swedish lake. Virtually all the lands surrounding the Baltic were sovereign Swedish land. And Peter the Great was hungry for a Baltic port, which he founded in 1703: Saint Petersburg.

3: Brands, 2012, p. 123.

†: A “Parthian Shot” is a horse archer in feigned retreat turning his body backwards firing a recurved bow at full gallop at an enemy in pursuit. “Parting shot” is a modern English idiomatic derivative of “Pathian Shot.”

‡: Sweden fought for another twelve years. Russia did not sign a separate peace, like his allies had before him. Peter honored his treaty obligations with his partners to the letter.

¤: Mikabridze, 2014, p. 92.