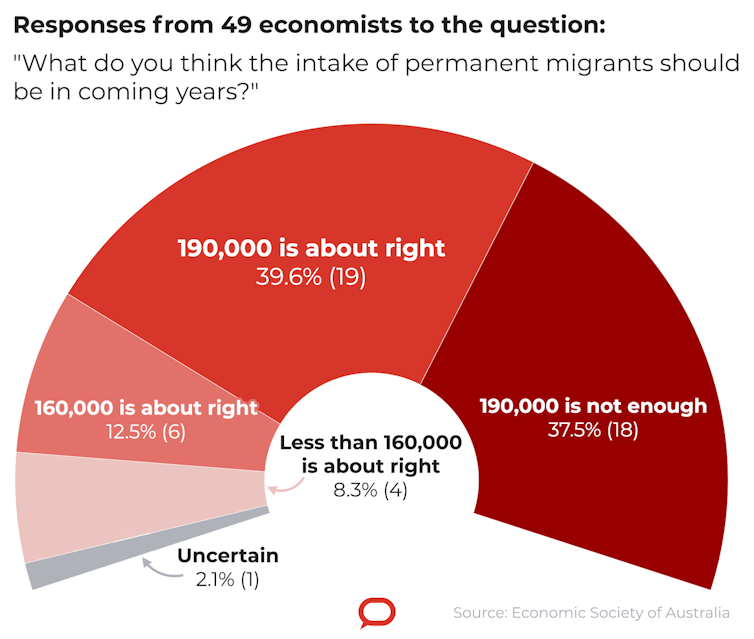

Australia’s leading economists have overwhelmingly endorsed a return to the highest immigration intake on record, saying Australia should aim for at least 190,000 migrants per year as it opens its borders, up from the target of 160,000 per year set ahead of COVID.

More than a third of those surveyed believe 190,000 isn’t enough, arguing that a “catch up” will show Australia is open to the world.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison cut Australia’s migration ceiling from 190,000 to 160,000 places per year in March 2019, in order to “tackle the impact of increasing population in congested cities”.

The 49 economists who took part in the Economics Society of Australia poll were selected by their peers for their expertise in macroeconomics, microeconomics and economic modelling. One is a member of the Reserve Bank board.

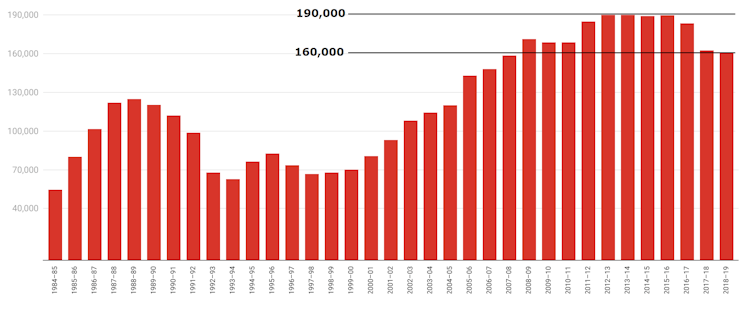

Ahead of COVID, Australia’s permanent intake has only been as high as 190,000 on five occasions, during the five years 190,000 was the official target.

Annual migrant intake in the years leading up to COVID

The government’s intergenerational report released mid last year assumed a return to an intake of 190,000 per year in 2023-24.

Only four of the 49 economists surveyed by The Economic Society and The Conversation wanted less migration than Australia had going into COVID.

Their concerns were that growing population numbers put pressure on “fragile resources and infrastructure”. Slower population growth would “ease pressures on the environment, housing prices, infrastructure and emissions”.

Adelaide University labour market specialist Sue Richardson said there was no evidence high levels of migration raised GDP per person, as opposed to GDP.

Congestion and the environment matter

“In terms of living standards, it is the per capita measure that matters,” she said. “And it should be adjusted for increased traffic congestion, urban density and pressures on the health and other important social systems.”

The six economists who thought an annual intake of 160,000 was about right made the point that what mattered more was the composition of the intake. There should be less unskilled migration, more skilled migration and a “decent humanitarian program”.

The 19 economists who went for 190,000 argued less would show a “lack of ambition” for lifting economic growth.

Helen Silver, chief general manager at Allianz Australia and a former head of Victoria’s Department of Premier and Cabinet said a higher target would be both a “catch up” and would act to symbolise Australia was more open to the world.

Australia benefits from being open

Any target would need to be flexible and responsive to the capacity of Australia’s heath and other systems given the ongoing pandemic.

Melbourne University economist John Freebairn said a larger population would enable Australia to capture economies of scale and fill gaps in high skill and low skill jobs caused by labour market rigidities and failures in training systems.

It would increase the government’s tax take net of spending and help build a more dynamic and interesting society, as it had in the past.

The 18 economists (37.5% of the total) who said 190,000 was not enough argued that Australia’s status as a nation of immigrants gave it a formidable advantage.

190,000 could be considered a floor

UNSW economist Gigi Foster said in the wake of Australia’s responses to COVID its challenge was not so much what target to set, but rather how to convince immigrants to come here.

Melbourne University ‘s Chris Edmond said if Australia had the same per capita target as Canada it would have a permanent intake of 250,000 per year.

The University of Sydney’s James Morely said 190,000 was less than 1% of the population and was in any event not a target for net migration as that would be determined by the number of Australians who left and returned, and the number who came in temporarily under other schemes.

Given low birth rates and a need for a balanced age profile Australia should probably target permanent visas of 320,000 - 1.25% of the current population.

RMIT’s Leonora Risse said what mattered was that the migration intake was accompanied by policies designed to ensure migrants reached their potential.

When considering an upper limit on migration, we should keep in mind that 30% of all Australians were born overseas. For 20% of Australians, one or both parents were born overseas. Australia would not be what it was were it not for migration.

Notably absent from most of the 49 responses was discussion of the impact of migration on wages and the employment of locals.

The experts surveyed seemed to regard these impacts as not particularly big in either direction compared to the impacts of migration on dynamism, Australia’s place in the world, and its environment, infrastructure and social cohesion.

Detailed responses:

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.