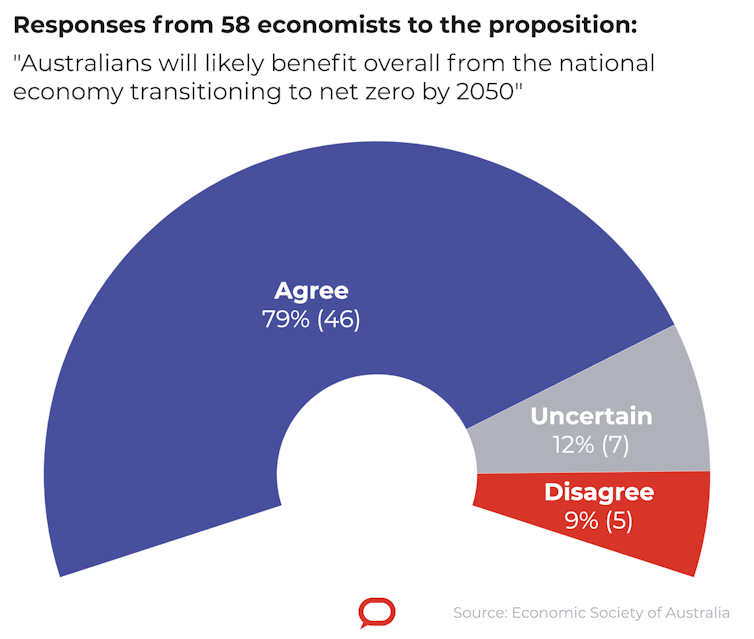

Eight in ten of Australia’s leading economists back action to cut Australia’s carbon emissions to net-zero.

Almost nine in ten want it done by a carbon tax or a carbon price – mechanisms that were explicitly rejected at the 2013 election.

The panel of 58 top Australian economists selected by the Economic Society of Australia wants the carbon price restored to the public agenda even though it was rejected seven years ago, some saying Australia’s goods and services tax was rebuffed in 1993 and then restored to the public agenda seven years later.

Among those surveyed are former heads of government departments and agencies, former International Monetary Fund and OECD officials and a former and current member of the Reserve Bank board.

Asked ahead of November’s Glasgow climate talks whether Australia would likely benefit overall from the national economy transitioning to net-zero emissions by 2050, 46 of the 58 said yes.

The response is at odds with the previous positions of groups such as the Business Council of Australia which in the leadup to the 2019 election labelled Labor’s proposed steps towards net-zero “economy wrecking”.

This month the Business Council backed net-zero by 2050, and produced modelling suggesting it would make Australians A$5,000 better off per year.

Only one net-zero doubter

Only five of the 58 economists surveyed disagreed with the proposition that cutting Australia’s emissions to net-zero would leave Australians better off.

Of those five, only one doubted that cutting global move emissions to net-zero would leave Australia better off. The others believed that even if a global move to net-zero did leave Australians better off, it was likely to happen anyway, meaning Australia wouldn’t need to act, a stance derided by others as “free-riding”.

“The argument that we are only a small percentage of global emissions holds no water either ethically or in terms of establishing and implementing a global agreement,” said Grattan Institute’s Danielle Wood. “If rich countries like Australia won’t do their fair share, this undermines the likelihood that others will.”

Others including Reserve Bank board member Ian Harper pointed out that Australian exporters faced punitive tariffs and lending and insurance embargoes unless Australia pulled its weight in reducing emissions.

His comments echo those of Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Guy Debelle and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg who have said that unless Australia takes action it will face reduced access to capital markets “impacting everything from interest rates on home loans and small business loans to the financial viability of large‑scale infrastructure projects”.

University of Melbourne economist Leslie Martin made the broader point that Australia had a lot to lose from rising temperatures if free-riding didn’t pay off.

“Although Australia could possibly free-ride on the efforts of other larger economies, it would suffer disproportionately if other countries chose to do the same” he said.

Only one overwhelmingly preferred option

Offered a choice of four options for rapidly reducing emissions, and asked to endorse only one, the economists surveyed overwhelmingly backed an economy-wide carbon price in the form of a carbon tax or market for emissions permits.

Of the 58 surveyed, 49 backed a carbon price, seven backed government support to develop and roll out emissions-reducing technologies, and one backed support for technologies that drew down carbon from the atmosphere.

None backed so-called “direct action” – the program of competitive grants for firms that cut emissions the government took to the last two elections.

“The less federal governments choose to involve themselves with the technical aspects of the alternatives at a micro scale the better,” said Lin Crase, a specialist in environmental management at the University of South Australia.

Crase said governments had shown themselves to be very bad at picking winners, but very good at putting in place broad settings that allowed the people and businesses closest to the action to pick winners.

Several of the economists surveyed said the government’s slogan of “technology, not taxes” set up a false distinction. Taxes could drive the switch to better technologies – ones chosen by the market rather than by government edict.

Australia’s carbon price was introduced in 2012 and abolished in 2014. Had it still been in place Australia would have at hand the tools it needed to get to net-zero.

Some of those surveyed said it was “too late” for a carbon price, partly because of politics and partly because of lost time.

Time for everything plus the kitchen sink?

Saul Eslake said Australia was no more likely to adopt an economy-wide carbon price than he was “to step in thylacine droppings on my front lawn of a morning”, the views of the OECD and the International Monetary Fund notwithstanding.

What was needed was everything possible, including the second-best option of direct action. John Quiggin said Australia needed direct action in the literal sense of government investment in renewable electricity and infrastructure.

Rana Roy said nothing should be ruled out, including the resurrection of a carbon tax or a carbon price, perhaps by a different name. An option rejected once was not rejected “for the rest of time”.

Others pointed to Australia’s natural advantages in solar, wind, geothermal energy and carbon removal via means such as reforestation and storing carbon in soil.

With the right settings in place, Australia could become a major producer of zero-emissions hydrogen, and an industrial powerhouse that used its own iron ore and green energy to export green steel to the world.

With one of the most important settings missing, Australia would find it harder.

Detailed responses:

![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.