When Labor leader Anthony Albanese couldn’t say whether the unemployment rate was 5% or 4% on Monday, he might have had a point.

It’s 4%. But for a decade – the entire decade leading up to COVID – it never strayed too far from five-point-something per cent.

Melbourne University labour market specialist Jeff Borland points out that in March 2010, Australia’s unemployment rate was 5.4%. Ten years later, before COVID changed things in March 2020, it was 5.3%.

In the years between, it briefly dipped to 4.9% (three times), climbed slowly as the mining boom wound down, edged above 6% in 2014 as the newly-elected Coalition government cut spending, and then fell back slowly towards what the Treasury then regarded as the long-term sustainable rate of 5%.

For much of Albanese’s time in parliament, from 1996 to now, it has been 5-6%.

And a case can be made that it is 5% right now.

Independent economist Saul Eslake says what he calls the “effective” rate of unemployment is indeed 5%. To the 607,900 officially unemployed Australians in February 2022 (the lowest slice of the population in decades), Eslake adds the historically high:

72,000 people who were counted as employed despite working zero hours, for what the Bureau of Statistics called “economic reasons” including being stood down or because there was insufficient work

59,000 people who were counted as employed despite working zero hours for reasons “other than economic”, including being on leave

The result is an unemployment rate of 5%, which doesn’t count as unemployed the 221,000 employed Australians who worked zero hours due to illness or injury – twice as many as before COVID.

The figures point to something real

But even Eslake’s effective rate of 5% is lower than before COVID.

The massive 26,000-household survey of employment conducted each month by the Bureau of Statistics is pointing to something real.

To get an idea of the scale of the bureau’s survey, compare it to the Essential and Newspoll surveys used to indicate how people are going to vote in the election. Essential surveys 1,000 people each time, Newspoll about 1,500.

The bureau surveys 26,000 households every month to obtain information on the employment status of about 50,000 people aged 15 and over. The scale of the operation is exceeded only by national elections every three years and the census every five years.

Australia’s biggest survey

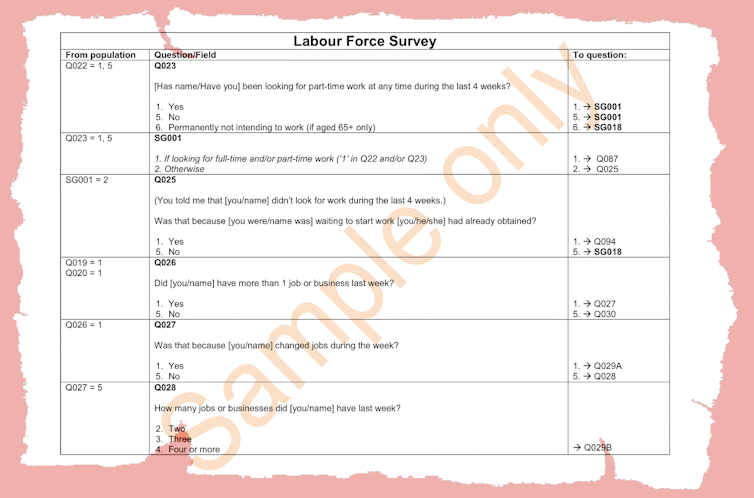

The survey asks first whether those surveyed worked in the previous week, then whether they were employed but away from work because of holidays, sickness or another reason. Then it asks about hours. Less than one hour (unless it was due to time off) counts as not working.

It is this definition (one hour a week = work) that generates so much of the mistrust of unemployment figures.

The bureau uses one hour per week as the cutoff because it has to use something and because every other comparable country has used it, since 1982.

Fewer than 50 of the 50,000 people surveyed each month report working only one hour, meaning the cutoff makes little difference.

If the bureau used a different cutoff, such as three hours per week, its employment numbers would be moving in the same direction.

It defines being unemployed as not being employed and looking for work. If you are not looking, you are “not in the labour force” and not counted as unemployed.

This is a problem when times are tough and people don’t bother to look (or can’t easily look, such as during lockdowns) and can mean that genuine unemployment is higher than the figures suggest.

More jobs on offer than ever before

But that isn’t a problem at the moment. So many jobs are on offer (423,500 – far more than ever before) that people who want work know it is worth looking.

More of the population aged 15 and over is in work than ever before. And almost all of the new jobs are full-time.

As would be expected given the shift to full–time work, casual employment (defined by the bureau as employment without paid leave) has fallen in recent years, rather than climbed as the opposition leader’s material suggests.

Women have benefited more from the improved jobs market than men, getting 240,000 of the 395,000 new places created over the past year. Every age group up to 65 has more work than it did before.

We will get an inkling as to whether things will keep getting better on Thursday when the bureau releases the employment figures for March, and again just two days before the May 21 election, when it releases the figures for April.

The Treasury and the Reserve Bank are cautious, expecting unemployment to settle at 3.75% before (in Treasury’s case) gradually climbing back to 4.25%.

But private forecasters are bolder. Westpac is forecasting an unemployment rate of 3.25% by year’s end. Citibank is forecasting 3.3% by the end of this year and an extraordinary 3% by the end of 2024 – which would be a 60-year low not seen since 1974.

How to keep creating jobs with reopened borders

It is tempting to say what has happened with unemployment is the result of closed borders and slower population growth during COVID (more jobs per worker than there would have been). But the banks making those bold forecasts know the borders have been reopened.

New Zealand has enjoyed faster (although still slowed) population growth than Australia over a year in which its unemployment rate has slid to 3.2%.

What New Zealand, Australia and the other nations now enjoying unusually low unemployment have in common is out-sized government spending and record low interest rates during COVID to keep the economy afloat.

Spending and ultra low rates create jobs. If we keep them in place right up to the point where we create worrying inflation, we will be able to get even more Australians into jobs and, all being well, keep them there.

It’s the most important thing to grasp from what’s happened. More important than the exact rate of unemployment.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.