This… Sigh. Here's some stuff to read:

- Who owns Einstein? The battle for the world’s most famous face — Simon Parkin in the Guardian:

Albert Einstein died in 1955. In article 13 of his last will and testament, he pledged that his “manuscripts, copyrights, publication rights, royalties … and all other literary property” would, upon the deaths of his secretary, Helen Dukas, and stepdaughter, Margot Einstein, pass to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, an institution that Einstein cofounded in 1918. Einstein made no mention in his will about the use of his name or likeness on books, products or advertisements. Today, these are known as publicity rights, but at the time Einstein was writing his will, no such legal concept existed. When the Hebrew University took control of Einstein’s estate in 1982, however, publicity rights had become a fierce legal battleground, worth millions of dollars each year. […] Despite the university’s repeated successes in taking on alleged infringers, critics remain unconvinced that Einstein would have wanted any of this. In life, he resisted attempts to commercialise his identity. Why would he have changed this position in death? One American law professor, writing in the New York Times, described the institution and others like it as “the new grave robbers”. A lawyer for Time Inc called agents acting for the university a “group of tribal headhunters”. The manufacturer of a children’s novelty Einstein costume is among the scores of businesses to have protested against the university’s position, telling a reporter, “[The university] cannot ‘inherit’ rights from Albert Einstein which did not exist at the time of his death.” The university, meanwhile, claims it has not only the legal right, but also a moral duty to protect Einstein from those who would besmirch his name with dubious associations.

- Non Sequitur — by Wiley Miller:

- The Cantillon Effect and Stock Market Crashes — Matt Stoller:

Financial markets are critical in any free society, because they enable flexibility in production and distribution. Without the ability to borrow money, speculate, and go bankrupt, it is very difficult if not impossible to systemize innovation, kill off old and inefficient firms, or cater to consumer tastes. Yet, finance should be a

small

part of the economy, because speculation isn’t intrinsically valuable. Banks should serve production, providing capital to ventures that will eventually generate income. Sometimes, however, financiers are able to take control of production, and that leads to wild inefficiencies, speculation purely on asset price inflation, and eventually authoritarian politics. As economist John Maynard Keynes wryly put it, “When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.” That’s where we are now. Compensation for financial intermediaries has historically cost about 2% of GDP; today it’s at 9%. To put it differently, a small number of people are collecting hundreds of billions of dollars in fees running private equity funds, but private equity is no better (and probably worse) in terms of returns than public equity indexes. This is no way to run a country. In a society with a coherent social vision, people would get rich investing in baby formula production, or medical dye, or generic pharmaceuticals, all of which are in shortage. But instead, money has been flooding into cryptocurrencies, weird obvious scams like SPACs, and a manic art market. Christie’s, for instance, just sold a famous Andy Warhol painting, a 1964 silk-screen of Marylin Monroe. The work went for $195 million to an anonymous bidder, which is the size of the annual budget for a small city, like Norman, Oklahoma. When baby formula is in shortage and art markets are insane, the economy has clearly become the byproduct of a casino. […] Essentially, if you own assets or intangible capital assets, you’re doing great. If you rely on your income making or moving something, you’re not. Hence the shortage in stuff that needs to be made or moved like baby formula, and the surplus in bullshit like cryptocurrency.

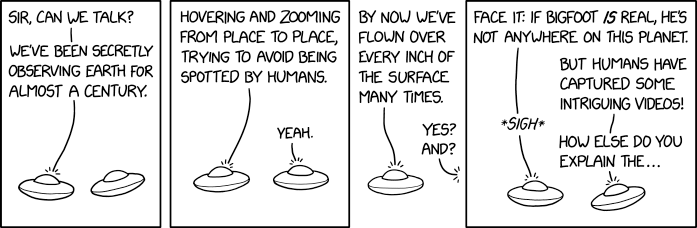

- xkcd — by Randall Munroe:

- Male economists are freaking out over a NYT profile — Emily Peck at Axios:

A handful of prominent male economists, including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, are freaking out — mostly on Twitter — about a weekend New York Times profile of economist Stephanie Kelton, known for her work on Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT. Why it matters: This Twitter-based econ fight is about more than one economist. It's an argument over a natural economic experiment — the U.S. government spending unprecedented sums to keep the economy from free-falling during COVID. And the gender dynamics — male economists piling on against a female economist and a female journalist, Times' reporter Jeanna Smialek, in ways distinctive from typical academic arguments — look terrible here.

- This Modern World — by Tom Tomorrow:

- The Rules of Commas — Ginny Hogan at McSweeney’s Internet Tendency:

You’ve probably used too many commas. In fact, I would go so far as to say you definitely have. As the last stage in your editing process, delete half of them. It doesn’t matter which ones. […] Commas should go in between items in a long list of things. If you don’t have a long list of things, stick the commas in between cushions on your couch. Someplace where they’ll be easy to find later. No one will care if you forget to use a comma unless you’re a woman with a Twitter account.

- The Oatmeal — by Matthew Inman:

- Elon Musk Reveals Jaw-Dropping Ignorance About Social Security — Jon Schwarz at the Intercept:

“Unfunded obligations” is the difference between Social Security’s current projected income and its current projected promised benefits. If these projections are correct, taxes will have to be raised by $60 trillion or benefits will have to be cut by that amount, or some combination of the two. But then there’s the “through the infinite horizon” part. This means that $60 trillion is Social Security’s unfunded obligations between now and the end of time. In other words, we don’t have to come up with $60 trillion right this second, as implied by Musk’s comparison to the present-day U.S. economy. We have an infinite amount of time to pay for this — or more conservatively, 5 billion years, when the sun will turn into a red giant and consume the Earth, at which point we’ll have bigger problems than Social Security. […] A reasonable person might ask whether humans can accurately predict the future over the next hundred, thousand, or million years. The answer, of course, is that we can’t. So why does the Social Security report do it? The infinite horizon number was first included in the annual Social Security report in 2003, thanks to pressure from right-wing wonks who hoped to see the program cut or dismantled.

- Doonesbury — by Garry Trudeau: