This month, I have been mostly reading:

- NATO — The Most Dangerous Military Alliance on the Planet — Chris Hedges in MintPress News:

The U.S. military, following its fiascos in the Middle East, has shifted its focus from fighting terrorism and asymmetrical warfare to confronting China and Russia. President Barack Obama’s national-security team in 2016 carried out a war game in which Russia invaded a NATO country in the Baltics and used a low-yield tactical nuclear weapon against NATO forces. Obama officials were split about how to respond. “The National Security Council’s so-called Principals Committee—including Cabinet officers and members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—decided that the United States had no choice but to retaliate with nuclear weapons,” Eric Schlosser writes in The Atlantic. “Any other type of response, the committee argued, would show a lack of resolve, damage American credibility, and weaken the NATO alliance. Choosing a suitable nuclear target proved difficult, however. Hitting Russia’s invading force would kill innocent civilians in a NATO country. Striking targets inside Russia might escalate the conflict to an all-out nuclear war. In the end, the NSC Principals Committee recommended a nuclear attack on Belarus—a nation that had played no role whatsoever in the invasion of the NATO ally but had the misfortune of being a Russian ally.” The Biden administration has formed a Tiger Team of national security officials to run war games on what to do if Russia uses a nuclear weapon, according to The New York Times. The threat of nuclear war is minimized with discussions of “tactical nuclear weapons,” as if less powerful nuclear explosions are somehow more acceptable and won’t lead to the use of bigger bombs. At no time, including the Cuban missile crisis, have we stood closer to the precipice of nuclear war.

- Public Transport Should Be Free — Chris Saltmarsh in Tribune:

Without a counter-measure like free public transport, extortionate fuel prices will drive social isolation and difficulties accessing employment—as well as hunger. But free public transport isn’t only crucial for addressing the cost of living crisis. It’s also a vital response to the climate emergency. In the UK, the transport sector is responsible for around one third of greenhouse gas emissions. Our transport system is dominated by private cars, one of the most inefficient modes of transport—they spend, on average, 95% of the time stationary, and take up huge amounts of space on roads compared to buses. We cannot simply swap all petrol and diesel cars for electric vehicles, because of the resource intensity of their manufacture, including the use of rare earth minerals. Instead, our environmental crises demand a wholesale shift from polluting forms of transport—including aviation, which is responsible for around 3.5% of global emissions—to low-carbon public transport. To realise these urgent societal shifts in transport use, policies to heavily discount public transport or make it free are key.

- Polarization — Jen Sorensen:

- The Forde Report and the Labour Right — Craig Murray:

It is often the case in official, or at least officious, documents that a simple bit of terminology betrays the entire mindset. The “Leaked Report” discovered a great many things, all of which the Forde Report finds to be essentially, and in detail, true. Yet the findings of the “Leaked Report” are described right from the terms of reference and throughout in the Forde exercise as “allegations”, while the findings of the Forde Report are, of course, “findings”. This is a form of dishonest declension: I make findings, you make allegations. […] Forde then attempts to maintain “balance” and treat all “factions” as equally authoritative and morally valid. That is the great failing of his report, and can be described in one sentence: Forde denies democracy. At no stage does the Forde report accept that Corbyn’s election by the mass membership gave him a democratic mandate that the paid HQ staff were obliged to follow. Rather Forde sees the HQ staff as guardians of a Blairite tradition that had an entirely equal right to determine events within the Labour Party, despite its leadership candidates being overwhelmingly rejected – several times – by the membership. Forde’s entire report is undermined by this false equivalence – the notion that both “factions” were equally responsible for the problems, and deserved equal weight and consideration.

- Boris Johnson’s Fall – and Ours — Robert Skidelsky in Project Syndicate:

We struggle to describe their character flaws: “unprincipled,” “amoral,” and “serial liar” seem to capture Johnson. But they describe more successful political leaders as well. To explain his fall, we need to consider two factors specific to our times. The first is that we no longer distinguish personal qualities from political qualities. Nowadays, the personal really is political: personal failings are ipso facto political failings. Gone is the distinction between the private and the public, between subjective feeling and objective reality, and between moral and religious matters and those that government must address. […] The other new factor is that politics is no longer viewed as a vocation so much as a stepping stone to money. Media obsession with what a political career is worth, rather than whether politicians are worthy of their jobs, is bound to affect what politically ambitious people expect to achieve and the public’s view of what to expect from them. Blair is reported to have amassed millions in speaking engagements and consultancies since leaving office. In keeping with the times, The Times has estimated how much money Johnson could earn from speaking fees and book deals, and how much more he is worth than May. In his resignation speech, Johnson sought to defend the “best job in the world” in traditional terms, while criticizing the “eccentricity” of being removed in mid-delivery of his promises. But this defense of his premiership sounded insincere, because his career was not a testimony to his words. The cause of his fall was not just his perceived lack of morality, but also his perceived lack of a political compass. For Johnson, the personal simply exposed the hollowness of the political.

- Bloom County — by Berkeley Breathed:

- Semiotics of dogs — Katrina Gulliver in Aeon:

Dog-fancying, and the arrival of pedigrees, came with the heady mix of science and sentimentality that marked the Victorian era. As a rising middle class started to focus on their own family trees, creating an ‘elite’ from new money, so dogs started to be classified too. […] Some breed fans still hope to find a more ancient lineage, to believe that their dogs come from a much older tradition than a bunch of Victorian pet buffs. As people hope to find luminaries in their own family tree, they want their dog to symbolise a link to antiquity. […] Although the prices are new (and spiralling partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic demand for puppies), the sentiment is not. In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), the economist Thorstein Veblen wrote of what he saw as overbred lapdogs: "The commercial value of canine monstrosities, such as the prevailing styles of pet dogs both for men’s and women’s use, rests on their high cost of production, and their value to their owners lies chiefly in their utility as items of conspicuous consumption." Physical distortion caused by breeding has led to extremes in the English bulldog, where 85 per cent of deliveries require a caesarean section, as the puppies’ heads are too large for the mother’s pelvis. These dogs could never have evolved this way in nature, they are entirely manmade, representing our domination over the breed.

- “Russian Propaganda” Just Means Disobedience — Caitlin Johnstone:

Ask anyone who says a criticism of the western empire’s Ukraine policy is “Russian propaganda” to name a critic of western Ukraine policy who they don’t consider a Russian propagandist. They won’t be able to. For them, disagreeing with one’s government about Ukraine is itself Russian propaganda. For empire apologists the measure of what constitutes “Russian propaganda” about Ukraine has nothing to do with whether or not what’s being said is true or valid; it’s literally just a question of obedience to one’s government about the decisions it’s been making with regard to that nation. If the measure of whether something qualifies as propaganda is defined entirely by whether it agrees with one’s government, then that measure is itself propaganda. That’s exactly what’s happening with criticism of the west’s interventionism in Ukraine. Something doesn’t have to come from Russia to be considered Russian propaganda, and its source doesn’t need to have any connection to the Russian government. It doesn’t even have to be false. All it needs to be is disobedient.

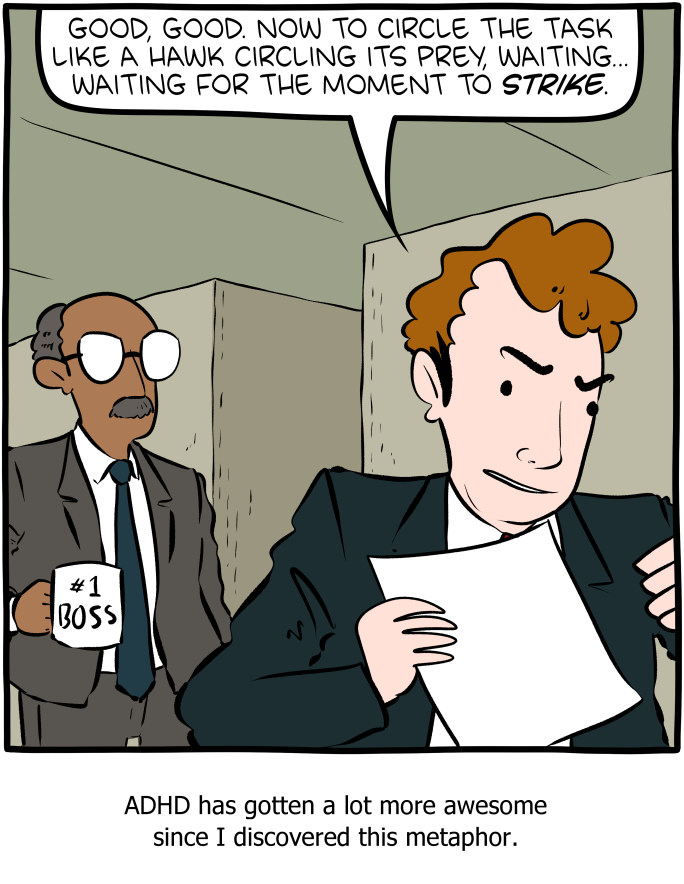

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal — by Zach Weinersmith:

- Gilding the cage of suburbia: farewelling Neighbours — Binoy Kampmark in Pearls and Irritations:

In Australian crowds, [Arthur Koestler] detected a conformism that produced a mass loneliness. They, his nose sensed, reeked of “loneliness – you can feel it in the bus, in the pub, at the races, on the beach.” Neighbours battles loneliness in forced fashion, and in doing so gilds the suburban cage. It imports a provincial, romantic reading about Australia’s brutish urban landscape. It assumes, fantastically, that there are neighbours who care with almost nosy dedication, whom you would actually like to know rather than regard with an air of suspicion. Philippa Burne, sometimes writer for the series, can comment that, boring as that suburbia is, “for UK and overseas audiences it’s a peaceful, privileged life where you can spend half the day in the pub and still pay the mortgage and not be a drunk.” Ian Smith, who played the character of Harold Bishop and also had a hand in script writing, put it this way: “You could say hello to your doctor, who lived next door. You could call him by his first name. You would sometimes go to his swimming pool, he would sometimes come to your swimming pool. All these things that didn’t happen in the UK.” Smith might be particularly fond of doctors in a way others simply aren’t.

- Ignorance is not bliss — Peter May in Progressive Pulse:

Rishi Sunak reportedly has told Tory hustings that he will “take a tougher approach to university degrees that saddle students with debt, without improving their earning potential”. Yes he also wants to improve technical education but that looks like an concomitant attempt to prevent ordinary people learning other stuff, because they will not have the ‘earning potential’. What about their social potential? Or societal worth? As a former banker why is it surprising that he doesn’t mention this? As ever, the Tories don’t want people without resources to get what they consider ‘good’ educations, because they are saddled with debt. Funny that – you wonder whether it is rather that ordinary people might just start to realise how ground down they are.

- The great regression — Matt Alt in Aeon:

It’s tempting to frame the Great Regression as a reaction to the unique confluence of crises that have affected Western nations in the 21st century – a byproduct of the profoundly unnerving decade we are living in. But our global second childhood has roots that extend far back before the appearance of COVID-19, the divisive populism of the 2010s, or even the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy of 2008. In the 1990s, a precursor to our contemporary Great Regression emerged in a certain nation decades before it did in the rest of the planet. That nation is Japan, and its experiences suggest that when the youth and young adults of a hyper-connected post-industrial society lose faith in the future, a Great Regression is inevitable. To critics who see the adoption of childish sensibilities among adults as a kind of social disease, this might seem a grim conclusion. But Japan’s experience implies a startling corollary. Under the right circumstances, regression can nourish. It can be a form of progression, a form of experimentation and creative play. It can pave the way for new ways of thinking and living. It can spawn new trends and identities and lifestyles. These become essential tools for navigating the strange new frontiers of modern life – and, as we adopt them, they transform our definition of what it means to lead healthy ‘adult’ lives.

- Phil Are Go!: