Australia was sidelined by the US. America completely disregarded the concerns of its supposed ally under the Anzus Treaty, Australia was treated with contempt … And the end result of this war was that Australia lost 41 soldiers killed, 241 wounded and over 500 who have since committed suicide, for the Taliban to be replaced with the Taliban” – Hugh Poate, whose son, 23-yo Robert Poate, was murdered in Afghanistan by an Afghan National army soldier in 2012. Our American “friends” let the murderer go without even warning their Australianvassalsmates.

Foreign interference and, more broadly, influence is something that worries well-informed Australians. Well, to be precise, only some foreign interference worries Aussies. Apparently, we prefer to remain uninformed about some of it. You know, we don’t need to worry about foreign interference from our “friends”. You see, they love us and are benevolent, thus their interference is good. Australia and the US are “like-minded” nations, as has become fashionable to say.

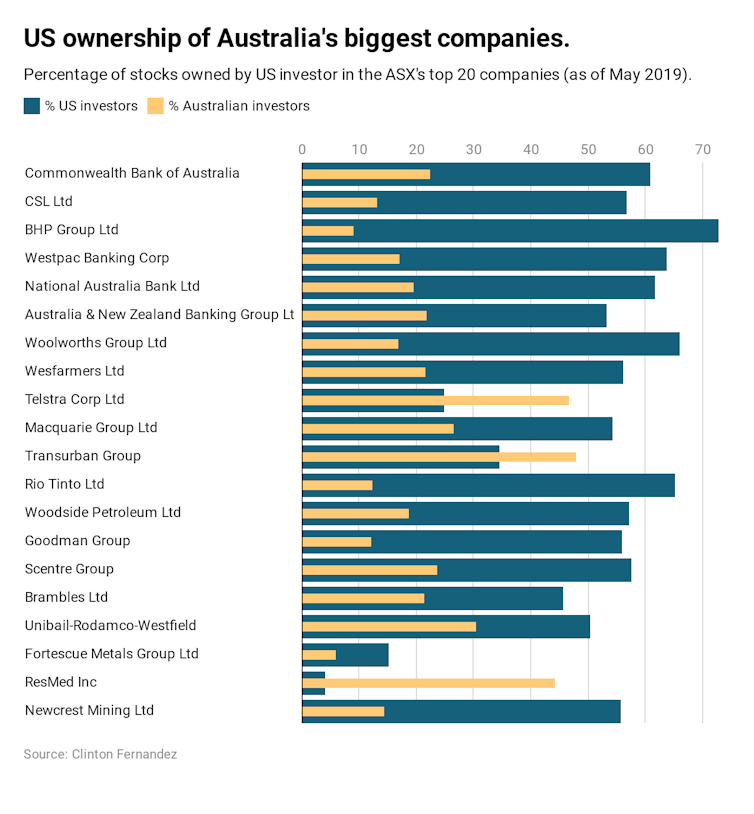

Worried about agents of foreign influence? Just look at who owns Australia’s biggest companies

The attention being given to possible covert influence being exercised by China in Australia shouldn’t distract us from recognising that very overt foreign influence now occurs through investment.

Right now US corporations eclipse everyone else in their ability to influence our politics, through their investments in Australian stocks.

Using company ownership data from Bloomberg, I analysed the ownership of Australia’s 20 biggest companies a few days after the 2019 federal election in May. Of those 20, 15 were majority-owned by US-based investors. Three more were at least 25% US-owned.

According to my analysis, all four of our big banks are majority-owned by American investors. The Commonwealth Bank of Australia, the nation’s biggest company, is more than 60% owned by American-based investors.

So too are Woolworths and Rio Tinto. BHP, once known as “the Big Australian”, is 73% owned by American-based investors.

The ASX’s top 20 companies make up close to half of the market capitalisation of the Australian Securities Exchange.

Such a concentration of foreign ownership should be a concern regardless of how much we see the US as an ally committed to liberal-democratic values, and appreciate that US corporate interests are not necessarily monolithic or necessarily exercised in accordance with a government agenda.

Nonetheless, under so-called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) clauses, which the US government has systematically pushed in its trade deals with other nations, US corporate investors are getting unprecedented rights in foreign markets.

ISDS provisions mean a foreign investor can sue a government for compensation in an international tribunal if the government makes any change in law or policy that “harms” an investment. This is something no Australian citizen can do.

Philip Morris’ smoking gun

Since I did my analysis, the composition of the ASX top 20 has changed. The bottom four companies – Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, Fortescue Metals Group, ResMed and Newcrest Mining – have made way for Insurance Australia, Suncorp, Amcor and South32.

This, however, has not signficantly altered the dominance of US investor interests.

It should also be noted that US investment firms also manage the wealth of foreign clients. But data from CapGemini and Merrill Lynch suggest the majority of assets the firms manage are American-owned, even if the precise number cannot be determined.

There are arguably good grounds to include ISDS clauses in free-trade agreements, but the potential downside is exemplified by the case of tobacco giant Philip Morris, which challenged Australia’s plain-packaging laws for cigarette packs.

The US company did so by moving ownership of its Australian operations to Hong Kong and then using the ISDS clause embedded in an investment treaty between Australia and Hong Kong. It used the clause to argue the Australian government’s law amounted to unjust confiscation of trademarks and intellectual property.

The ISDS clause gave Philip Morris privileges no Australian company or individual had. Even though it lost, having its case thrown out on the grounds it was an abuse of process, it only had to pay half of Australia’s costs, which added up to almost A$24 million.

Jonathan Bonnitcha and his co-authors argue in their book The Political Economy of the Investment Treaty Regime that when states take legal action against each other, they have an incentive not to advance legal arguments that may backfire on them down the track. They have defensive interests.

Under ISDS clauses, though, private investors don’t have defensive interests. States cannot commence proceedings against them. They can attack with adventurous legal arguments, and not worry about defending themselves from those same arguments down the road.

Unlike courts, ISDS arbitrations lack standardised rules of procedure. Predictability of outcomes is much lower. Proceedings are private, not public. Only the final outcome is routinely available, and only if the parties agree.

Transparency matters

Under foreign influence transparency laws that came into effect in March, “foreign principals” must declare their role in influencing governmental and political decision-making. Foreign principals include governments, organisations, individuals and “entities”.

A company falls within the definition of a “foreign government-related entity” if its directors are accustomed or under an obligation to being influenced by a foreign government or political organisation, or if these governments and organisations hold more than 15% of the company’s shares or voting power, or can appoint at least 20% of the company’s board of directors; or otherwise exercise substantial control.

All well and good. Australian democracy benefits when foreign efforts to influence policies are conducted in an open and transparent manner.

But should not there be equal accountability and transparency over who owns our most powerful companies, the privileges they have under ISDS provisions, and what happens in any dispute proceedings?![]()

Clinton Fernandes, Professor, International and Political Studies, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.