Ten years ago, in the lead-up to Australia’s short-lived carbon price or “carbon tax” (either description is valid), the deepest fear on the part of businesses was that they would lose out to untaxed firms overseas.

Instead of buying Australian carbon-taxed products, Australian and export customers would buy untaxed (possibly dirtier) products from somewhere else.

It would give late-movers (countries that hadn’t yet adopted a carbon tax) a “free kick” in industries from coal and steel to aluminium to liquefied natural gas to cement, to wine, to meat and dairy products, even to copy paper.

It’s why the Gillard government handed out free permits to so-called trade-exposed industries, so they wouldn’t face unfair competition.

As a band-aid, it sort of worked. The firms with the most to lose were bought off.

But it was hardly a solution. What if every country had done it? Then, wherever there was a carbon tax (and wherever there wasn’t), trade-exposed industries would be exempt. The tax wouldn’t do enough to bring down emissions.

We are about to face carbon tariffs

The European Union has cottoned on to the imperfect workarounds introduced by countries such as Australia, and is about to tackle things from the other direction.

Instead of treating foreign and local producers the same by letting them both off the hook, it’s going to place both on the hook.

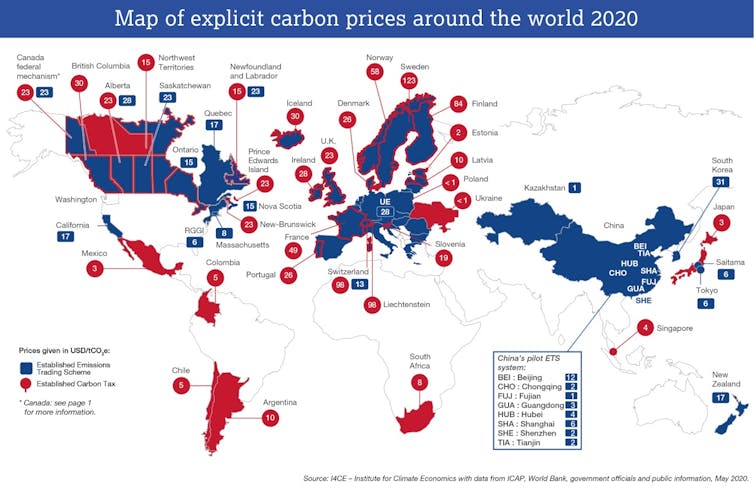

It’s about to make sure producers in higher-emitting countries such as China (and Australia) can’t undercut producers who pay carbon prices.

Unless foreign producers pay a carbon price like the one in Europe, the EU will impose a carbon price on their goods as they come in — a so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, or “carbon tariff”.

Australia’s Energy Minister Angus Taylor says he is “dead against” carbon tariffs, a stance that isn’t likely to carry much weight in France or any of the other 26 EU nations.

Australia is familiar with the arguments for them

From 2026, Europe will apply the tariff to direct emissions from imported iron, steel, cement, fertiliser, aluminium and electricity, with other products (and possibly indirect emissions) to be added later.

That is, unless they come from a country with a carbon price.

Canada is also exploring the idea, as part of “levelling the playing field”. So is US President Joe Biden, who wants to stop polluting countries “undermining our workers and manufacturers”.

Their arguments line up with those heard in Australia in the lead-up to our carbon price: that unless there’s some sort of adjustment, a local carbon tax will push local employers towards “pollution havens” where emissions are untaxed.

In practice, there’s little Australia can do to stop Europe and others imposing carbon tariffs.

As Australia discovered when China blocked its exports of wine and barley, there’s little a free trade agreement, or even the World Trade Organisation, can do. The WTO was neutered when former US President Donald Trump blocked every appointment to its appellate body, leaving it unstaffed, a stance Biden hasn’t reversed.

Even so, the EU believes such action would be allowed under trade rules, pointing to a precedent established by Australia, among other countries.

Legality isn’t the point

When Australia introduced the Goods and Services Tax in 2000, it passed laws allowing it to tax imports in the same way as locally produced products, a move it has recently extended to small parcels and services purchased online.

Trade expert and Nobel Prizewinning economist Paul Krugman says he is prepared to argue the toss with politicians such as Australia’s trade minister about what’s legal and whether carbon tariffs would be “protectionist”.

But he says that’s beside the point:

Yes, protectionism has costs, but these costs are often exaggerated, and they’re trivial compared with the risks of runaway climate change. I mean, the Pacific Northwest — the Pacific Northwest! — has been baking under triple-digit temperatures, and we’re going to worry about the interpretation of Article III of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade?

And some form of international sanctions against countries that don’t take steps to limit emissions is essential if we’re going to do anything about an existential environmental threat.

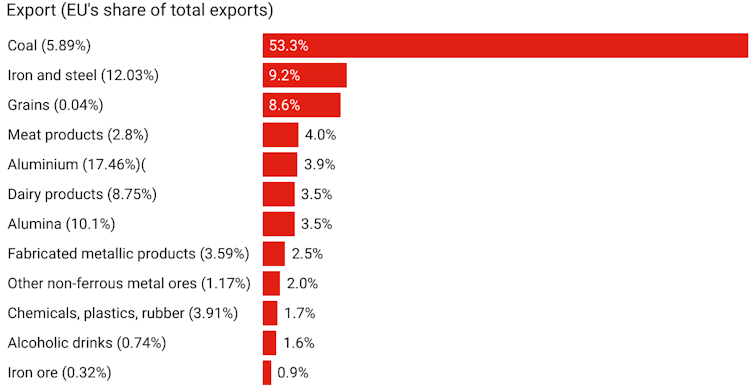

Victoria University calculations suggest Europe’s carbon tariffs will push up the price of imported Australian iron, steel and grains by about 9%, and drive up the price of every other Australian import by less, apart from coal whose imported price would soar by 53%.

The tariffs would be collected by Europe rather than Australia. They could be escaped if Australian makers of iron, steel and other products can find ways to cut emissions.

Increase in price of exports to EU under carbon border adjustment mechanism

The tariffs could also be avoided if Australia were to introduce a carbon price or something similar, and collected the money itself.

This makes a compelling case for another look at an Australian carbon price. If Australian emissions are on the way down anyway, as Prime Minister Scott Morrison contends, it needn’t be set particularly high. If he is wrong, it would need to be set higher.

One thing the sad story of Australia’s on-again, off-again, now on-again (through carbon tariffs) history of carbon pricing has shown is that politicians aren’t the best people to set the rates.

In 2011, Prime Minister Julia Gillard set up an independent, Reserve Bank-like Climate Change Authority to advise on the carbon price and emissions targets, initially chaired by a former governor of the Reserve Bank.

Astoundingly, despite attempts to abolish it, it still exists. It might yet have work to do.

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.