Reading

In an apparent nod to Israel, some Democrats want to give Trump power to defend “an ally or partner of the United States from imminent attack.”

The post War Powers Resolution From House Democratic Leaders May Not Limit Trump’s War Powers appeared first on The Intercept.

Experience a heart attack while working in the herb garden.

Wonder what its middle school bully is doing now.

Show up to court in a white linen suit.

Drape itself face down over an ottoman in a fit of ennui.

Adjourn to the study for brandy and cigars.

Yearn, long, or pine.

Suspect that something evil has happened in this very room.

Fall for Doreen.

Lose its sense of time in a Hudson News and miss its flight.

Have a least-favorite roommate.

Cultivate a neglectful-dad-type mystique.

Admire the voluptuous nature of a cloud.

Climax in unison with its lover.

Hunt down the nautical animal that took its appendage.

Obtain a meditative state and lose it.

Extend a too-firm handshake to its daughter’s boyfriend.

Swiftly transition from self-loathing to acceptance at the sight of its dead and unwatered fig plant.

Twirl a little parasol and play hard-to-get with the boys at the race track.

Rid itself of the feeling that this yoga retreat is a scam.

Chug this Modelo in front of everyone.

Become shy about its weird areolas.

Party leaders haven’t decided whether to rally behind Zohran Mamdani or a centrist backed by the Israel lobby.

The post N.Y. Dems Face Choice Between Voters’ Chosen Candidate and Disgraced Adams, Cuomo appeared first on The Intercept.

Francisco Goya’s etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters was an artist’s stern warning of the hideous forces unleashed in the mind when reason lowers its guard. Today, stablecoins are the gruesome forces being released into the global economy as President Trump’s crypto dreams, unchecked by reason, morphed into the GENIUS Act. Stablecoins are the […]

The post The stablecoin time bomb hidden in Trump’s GENIUS act: Prepare for the next financial meltdown – UNHERD, 19 JUNE 2025 appeared first on Yanis Varoufakis.

DrupalCon has always been a conference by the community, for the community—and as we look ahead to DrupalCon North America 2026 in Chicago, we’re making thoughtful changes to ensure it continues to reflect those values.

After a successful DrupalCon Atlanta, we’ve taken time to reflect, gather feedback, and make updates that prioritize access, sustainability, and community connection. Each of the changes outlined below is rooted in one or more of these values—whether it's improving affordability, building lasting relationships, or creating a more efficient and inclusive event experience. With guidance from the DrupalCon North America Steering Committee, we’re excited to share a refreshed ticket structure, updated volunteer policies, a reimagined Expo Hall, and a renewed focus on summits, trainings, and collaboration.

For the most accurate total walk time, select all that apply.

You are wearing sensible shoes -1 min

You are wearing heels +6 min

You are wearing heels (but you are Sarah Jessica Parker) -5 min

You are over 5′10″ -1 min

You are under 5′2″ and staging a protest against your long-legged friends +5 min

You get a CNN alert that starts with: “White House hits Harvard with…” +2 min

You’re having a main-character moment while listening to Rihanna’s “Bitch Better Have My Money” -2 min

You’re having a main-character moment while listening to the Beatles’ “The Long and Winding Road” +2 min

You’re having an unpaid non-union background extra moment +0 min

You are taking a phone call from your mom, and she has juicy hometown gossip +5 min

You are taking a phone call from your mom, and she wants to know what a Labubu is and where to buy one -1 min

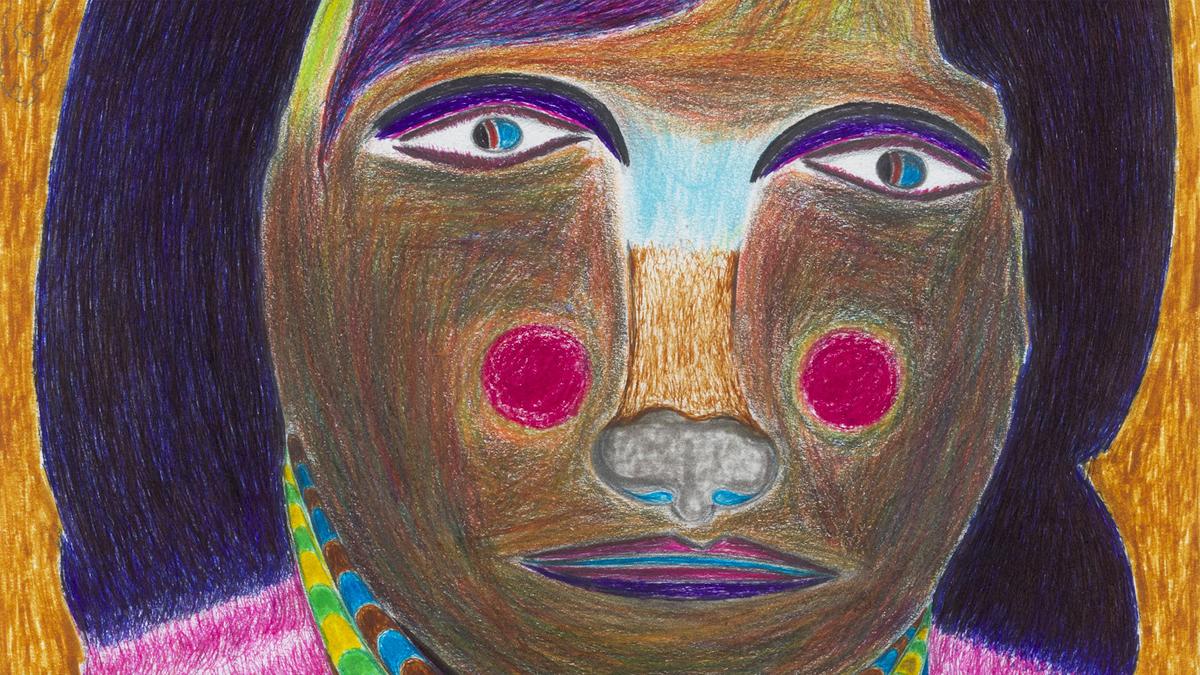

- by Aeon Video

After fleeing war-torn Liberia, an outsider artist creates haunting portraits while seeking asylum in the Netherlands

- Directed by Tal Amiran

It can be awkward at first, but there are specific methods you can use to spark an enjoyable chat with just about anyone

- by Michael Yeomans

The Trump administration is seeking deals with more and more nations to hold deportees — now with the blessing of the Supreme Court.

The post Trump’s Global Gulag Search Expands to 53 Nations appeared first on The Intercept.

Smoke and dust from fires could block the sun, but that’s not necessarily a good thing

The post The Weird Cooling Effect of Wildfires appeared first on Nautilus.

A simple test can peek into ivory to detect deception

The post An Elephant’s Tusk Never Forgets appeared first on Nautilus.